A few diabetes papers of interest

“Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, or insulin pump, therapy for individuals with type 1 diabetes has increased gradually since the 1980s. Yet, a Cochrane review concluded in 2010 that although some evidence indicates that insulin pumps improve glycemic control compared with standard multiple daily injection (MDI) therapy, insufficient evidence exists regarding mortality, morbidity, and costs (1). A systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies summarized comparisons of insulin pump and MDI therapy using model analyses to describe the expected impact on long-term costs, development of complications, and quality of life (2). Five of the studies reported long-term discounted incremental costs of insulin pumps of $20,000–$40,000, whereas two studies reported lower and one higher additional costs for insulin pump therapy. However, real-world data on health care and societal costs of insulin pump therapy compared with MDI therapy are scarce. […] Data from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR) have shown a lower incidence of some cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality for individuals with type 1 diabetes on insulin pump therapy in 2005–2012 (5). Registration of insulin pump therapy started in 2002 in the NDR, and use of pump therapy among individuals with type 1 diabetes increased from 10% in 2002 to 22% in 2015 (6). A relevant research question from a health care planning perspective is whether real-world data match earlier model-based predictions for differences in resource use and costs. We investigated from a societal perspective costs of continuous insulin pump and MDI therapy in clinical practice for individuals with type 1 diabetes using the NDR and a 9-year observational panel from national health and socioeconomic data registers.”

“The final analysis set included data in 2005–2013 for 14,238 individuals with type 1 diabetes, of whom 4,991 had insulin pump therapy (598 individuals switched to pump therapy in 2005 or later after original inclusion as control subjects with MDI). We had 73,920 person-years of observation with a mean follow-up of 5 years per subject. […] The distribution of annual costs was left-skewed with a tail of observations with high costs, although the most person-years incurred costs corresponding to typical insulin therapy and up to two regular follow-up appointments […] The difference in the annual total cost between the therapy groups was $3,923 (95% CI $3,703–$4,143). […] The difference in annual medication costs, including disposables, was $3,600, indicating that they contributed significantly to overall annual cost differences. Pump users had more outpatient appointments (3.8 vs. 3.5 per year; P < 0.001) and were less likely to have person-years without use of outpatient or inpatient care (9% vs. 12% of person-years). Even with a median duration of diabetes of 21 years at baseline, the mean cost per patient-year of cardiovascular comorbidities and diabetic complications was low because of the overall low rates of events. […] Total annual costs increased with age for both insulin therapies, and pump therapy was associated with higher costs across age-groups. However, the cost increments for insulin pump therapy decreased with age (differences ranging from 56% for those 18–27 years of age to 44% for those ≥48 years [reference: MDI 18–27 years]). Total costs were higher for women but decreased with years of education and disposable income. […] The level of HbA1c at baseline affected the differences in average annual cost between study groups: the smallest difference ($2,300) was observed for individuals with HbA1c ≥8.6% (≥70 mmol/mol) and the greatest difference for individuals with HbA1c 6.5–8.5% (48–69 mmol/mol) at baseline [pump $12,824 vs. MDI $8,083; P < 0.001, US].”

“The study cohort was young (mean baseline age 34 years) with relatively few diabetic complications in both study groups. For instance, 1.5% of person-years had a cardiovascular event, and 5% had at least one health care contact with a cardiovascular diagnosis.

Observational studies provide a better indication of what is achieved in daily medical practice than randomized controlled studies (12). The strength of this observational study is the size and completeness of the study population, with virtually all adults with type 1 diabetes in Sweden included, longitudinal national register data, and a matching technique that accounts for time-variant variables, including diabetes duration, diabetes-related conditions and comorbidities, and demographic and socioeconomic factors. With the use of time-varying propensity scores, we allowed selected MDI control subjects to switch to pump therapy rather than to condition their eligibility or noneligibility on a future therapeutic change. The plentiful data allowed us to match two control subjects to each pump user to account for the variance in cost variables and enabled extensive subgroup and sensitivity analyses.”

“We observed only a few deaths (n = 353 [2.5% main analysis sample], no difference pump vs. MDI [OR 0.98 (95% CI 0.79–1.23)]) and similar rates of cardiovascular disease for pump and MDI in this study, except for borderline significantly fewer events with angina in the pump group. A heterogeneous distribution of events was found across nontreatment characteristics: ∼70% of all cardiovascular events occurred among individuals 48 years of age or older, and >90% of the events occurred among individuals with diabetes duration ≥20 years at baseline.

A lack of comparable calculations of total costs of diabetes treatment has been published to date, but cost-effectiveness studies of pump and MDI therapy have predicted long-term costs for the two treatment methods. Roze et al. (2) performed a meta-review of model-based studies that compared pump therapy and MDI, concluding that pump therapy can be cost effective. Published models have identified change in HbA1c and reduction in number of hypoglycemic events as important drivers of costs. A Swedish health technology assessment review in 2013 did not find evidence for differences in severe hypoglycemia between pump therapy and MDI but identified indications of lower HbA1c (13). […] Subgroup analyses by age indicated that the value of improved prevention may take time to manifest. Approximately one-quarter of additional annual costs for individuals with type 1 diabetes age ≥48 years (∼25% of the cohort) could be prevented with insulin pump therapy.

Whether insulin pump therapy is cost efficient ultimately depends on therapeutic effects beyond resource use and costs as well as on how much the payer is prepared to invest in additional quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). If the payer’s cost-effectiveness threshold is $50,000 per QALY gained, treatment needs to provide an average annual additional 0.1 QALY or, on the basis of the subgroup analyses, gains in the range of 0.06–0.12 QALY. Similarly, with a threshold of $100,000, the required gain in annual QALYs would have to be between 0.03 and 0.06. The average cost difference between insulin therapies in this study and a 20-year time horizon roughly correspond to a discounted (3%) lifetime cost difference of $62,000. The corresponding cost for a 40-year time horizon is $95,000. Previous model-based cost-effectiveness analyses have reported expected discounted QALY gains for a lifetime in the range of 0.46–1.06 QALYs, whereas the estimates of the increase in discounted lifetime costs varied (2).”

…

“One of the most devastating complications of diabetes is chronic kidney disease. Relative to the general population, persons with diabetes have a 5- to 13-fold risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (4–6). ESRD extensively increases risk of death among patients with diabetes (7–9), and diabetes is the most common cause of ESRD in most industrialized countries (10); a study of 18 European countries showed that type 2 diabetes was the most frequent renal disease leading to initiation of renal replacement therapy (11).

Most earlier studies of the incidence of ESRD in diabetes have used prevalence cohorts, which means that patients have not been followed since their diabetes diagnosis. Patients with all types of diabetes typically have been included, and the incidence rate of ESRD has been 1–9 per 1,000 patient-years (4,12–14), with larger estimates among African Americans and those with a longer duration of diabetes. Notably, a prevalence cohort study from Italy including only patients with type 2 diabetes showed that only 10 of 1,408 patients developed ESRD over a 10-year follow-up (15). To our knowledge, only two inception cohort studies have addressed the incidence of ESRD. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study followed 5,097 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, only 14 of whom required renal replacement therapy during the median follow-up of 10.4 years (16). However, the cumulative risk was not computed, and any subgroup analyses would not have been possible because of the small number of patients who developed ESRD. A population-based study from Saskatchewan, Canada, included 90,429 incident cases of diabetes among the adult study population, and the results showed an almost threefold risk of ESRD among indigenous patients (17). Among nonindigenous patients, the cumulative incidence of ESRD was ∼1–2% at 20 years since the diabetes diagnosis.

We and others have estimated the cumulative risk of ESRD in inception cohorts of patients with type 1 diabetes (18–21). Although type 2 diabetes is a major cause of ESRD, cumulative risk of ESRD after type 2 diabetes has been diagnosed is not well known. Here, we present the cumulative risk of ESRD during a 24-year follow-up of a nationwide population-based cohort of 421,429 patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in 1990–2011.”

“Of 421,429 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in 1990–2011, 1,516 developed ESRD and 150,524 died before the end of 2013. The total number of patient-years of type 2 diabetes was 3,458,797 […]. The median follow-up was 6.82 years. A sex difference was found for age distribution: 70% of women and 55% of men were 60 years or older when type 2 diabetes was diagnosed. […] The cumulative risk of ESRD was 0.29% at 10 years and 0.74% at 20 years since the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. […] Men had a 93% higher risk of ESRD than women. […] this male predominance is a common finding for all causes of ESRD (10). […] As an alternative analysis, the incidence rate of ESRD was calculated among all prevalent cases of type 2 diabetes in the time periods 1990–1999 and 2000–2011, thus including patients who were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes before 1990 but who contributed patient-years in 1990–2013 […]. During a total of 4,345,251 patient-years, 2,127 patients developed ESRD, resulting in an incidence rate of 0.49 per 1,000 patient-years (95% CI 0.47–0.51). The incidence rate was higher among men (0.66 [95% CI 0.63–0.70]) than among women (0.33 [95% CI 0.31–0.35]) and in 2000–2013 (0.53 [95% CI 0.51–0.56]) than in 1990–1999 (0.37 [95% CI 0.34–0.41]). The incidence rate of ESRD had increased most among men older than 70 years. For both men and women, the incidence rate of ESRD peaked among those aged 60–79 years.”

“Among patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes between 1990 and 2011, the cumulative risk of death was 34% at 10 years and 64% at 20 years since the diagnosis of diabetes. […] Patients aged 70–79 years when diabetes was diagnosed had an eightfold risk of death during the follow-up compared with those aged 40–49 years. When calculating HR for death, occurrence of ESRD was included in the multivariable model as a time-dependent variable […], and ESRD increased the risk of death 4.2-fold during follow-up. […] In the interaction analysis, sex modified the effects of age and ESRD on HR for death. Among men, ESRD increased risk of death 3.8-fold and among women, 5.6-fold. Age (70–79 vs. 40–49 years) showed an HR for death of 7.4 among men and 9.8 among women. Also, a statistically significant interaction occurred between age and ESRD during follow-up, showing a weaker association between ESRD and risk of death among those aged 70 years or older (HR 3) than among those younger than 60 years (HR 5).”

“Our study shows that risk of ESRD is small among people with type 2 diabetes. This may seem unexpected, because a substantial proportion of patients are entering early stages of chronic kidney disease, with 25% of patients having microalbuminuria and 5% having macroalbuminuria 10 years after their diabetes diagnosis (16). These early stages of kidney disease are associated with increased premature mortality; this contributes to the fact that relatively few patients develop ESRD, as death is a common competing risk event. However, diabetes is the most common cause of ESRD in most industrialized countries, and because of a high and increasing prevalence of diabetes among the general population, a considerable absolute number of patients with type 2 diabetes need dialysis therapy (10,11). Our findings are important for clinicians who inform patients with type 2 diabetes about the associated risks and complications. […] Notably, people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at an older age have a lower risk of ESRD and a higher risk of death than those diagnosed at a younger age. The cumulative risk of ESRD and death has decreased since the early 1990s among people with type 2 diabetes.”

…

“In a population-based observational study, HbA1c for 451 patients diagnosed with diabetes before 35 years of age during 1983–1987 in southeast Sweden was followed for up to 18–24 years from diagnosis. Long-term mean weighted HbA1c (wHbA1c) was calculated. Retinopathy was evaluated by fundus photography and analyzed in relation to wHbA1c levels.”

“RESULTS Lower wHbA1c, diabetes onset ≤5 years of age, and diabetes onset before puberty, but not sex, were associated with longer time to appearance of simplex retinopathy. Proliferative retinopathy was associated only with wHbA1c. The time to first appearance of any retinopathy decreased with increasing wHbA1c. Lower wHbA1c after ≤5 years’ diabetes duration was associated with later onset of simplex retinopathy but not proliferative retinopathy. With time, most patients developed simplex retinopathy, except for those of the category wHbA1c ≤50 mmol/mol (6.7%), for which 20 of 36 patients were without any retinopathy at the end of the follow-up in contrast to none of 49 with wHbA1c >80 mmol/mol (9.5%). […] At the end of the follow-up only 54 patients (12.5%) had no signs of retinopathy and 145 (33.6%) had slight simplex, 175 (40.5%) moderate simplex, and 57 (13.2%) proliferative retinopathy.”

“CONCLUSIONS Onset at ≤5 years of age and lower wHbA1c the first 5 years after diagnosis are associated with longer duration before development of simplex retinopathy. There is a strong positive association between long-term mean HbA1c measured from diagnosis and up to 20 years and appearance of both simplex and proliferative retinopathy.”

“Complete avoidance of retinopathy in patients with type 1 diabetes evidently requires a very tight glycemic control, which is very difficult to achieve with the treatment tools available today and is also dangerous because of the risk of severe hypoglycemia (27). […] In clinical practice, it is of great importance to find the balance between the risk of potentially dangerous hypoglycemic events and quality of life and the risk of severe microvascular complications to be able to recommend an evidence-based optimal level of HbA1c both in the short-term and in the long-term. The observation that wHbA1c before and during puberty did not influence the prevalence of proliferative retinopathy at 20 years’ diabetes duration is of clinical importance in the setting of targets for glycemic control in young children for whom severe hypoglycemia might be especially dangerous.

Simplex retinopathy is not sight threatening, even if advanced simplex retinopathy is a risk factor for proliferative retinopathy (13). However, simplex retinopathy may regress, and in our study simplex retinopathy regressed in a group of patients with mean wHbA1c 7.0% (SD 0.7%) (53 [8] mmol/mol). Proliferative retinopathy is clinically more relevant and should be avoided. We previously showed that the threshold for proliferative retinopathy is higher than for simplex retinopathy (28). Proliferative retinopathy did not occur in this material in patients with wHbA1c <7.6% (60 mmol/mol), which indicates what should be an important goal for glycemic control. This is in close agreement with the position statement for type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents recently issued by the American Diabetes Association recommending an HbA1c target of <7.5% (58 mmol/mol) (31).

In summary, after 20 years of diabetes duration, there is a strong positive association between long-term mean wHbA1c followed from diagnosis and appearance of both simplex and proliferative retinopathy. Diabetes onset at <5 years of age and lower wHbA1c the first 5 years after diagnosis are associated with longer duration before development of simplex retinopathy but not proliferative retinopathy. Proliferative retinopathy does not appear in patients with wHbA1c <7.6% (60 mmol/mol).”

…

“Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a devastating condition accounting for 10–15% of all stroke cases. It is associated with a dismal prognosis, as only 38% of affected patients survive the first year (1).

Type 2 diabetes affects more than 415 million adults worldwide and is a well-known contributor to cardiovascular morbidity, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality (2). Although diabetes is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke (3), as yet there is no conclusive evidence for the association between diabetes and ICH, as previous studies showed conflicting results (4–8). […] We sought to determine 1) the association of diabetes and ICH and 2) the relationship between HbA1c levels and ICH in a large nationwide population-based cohort. […] We sought to determine 1) the association of diabetes and ICH and 2) the relationship between HbA1c levels and ICH in a large nationwide population-based cohort.”

…

Do keep in mind in the following that although the link between hemorrhagic stroke and diabetes is somewhat unclear (…for example: “in the Copenhagen Stroke Registry, hemorrhagic stroke was even six times less frequent in diabetic patients than in non-diabetic subjects (102). […] However, in another prospective population-based study DM was associated with an increased risk of primary intracerebral hemorrhage (103).”), the link between ischemic stroke and diabetes is strong and well-established – see the link for more details.

…

“This study is based on data from the computerized database of Clalit Health Services (CHS), which provides inclusive health care for more than half of the Israeli population. […] 313,130 patients had a preexisting diagnosis of diabetes and 1,167,585 individuals were without diabetes. Patients with diabetes had to have at least one test result for HbA1c in the 2 years before cohort entry (n = 297,486). Cohort participants (n = 1,465,071) were followed-up until reaching the study outcome (ICH), death, loss to follow-up, or end of follow-up at 31 December 2017 — whichever came first. […] The outcome of interest was ICH, defined as primary discharge diagnosis with ICH (ICD-9 code 431). […] Overall 4,170 patients had incident ICH during a mean (SD) follow-up of 7.3 (1.8) years and 10,730,915 person-years, reflecting an ICH crude incidence rate of 38.8 per 100,000 person-years. […] The strongest risk factors for ICH were prior ICH, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), use of anticoagulation, hypertension, alcohol abuse, male sex, Arab ethnicity, chronic liver disease, and older age.”

“Because of the large number of potential confounders, we performed adjustment for a disease risk score (DRS), a summary measure of disease probability. The DRS was estimated using a Cox proportional hazards regression model for ICH outcome that included most clinically relevant ICH risk factors and other clinical covariates likely to be correlated with ICH […]. In comparison with conventional multivariate analyses, adjustment for the single variable DRS increases the efficiency of the analyses (16,17). It has been shown than the DRS and propensity score methods had comparable performance and that DRS has an advantage when multiple comparison groups are studied (16,17). […] The crude incidence rate of ICH was 78.9 per 100,000 person-years among patients with diabetes and 29.4 per 100,000 person-years among patients without diabetes (crude HR 2.69 [95% CI 2.53–2.87]) (Table 2). Diabetes remained significantly associated with ICH after adjustment for DRS (1.36 [1.27–1.45]). […] The results were unchanged after exclusion of new cases of diabetes and after censoring at the time of new diabetes diagnosis occurring during follow-up: DRS-adjusted HR 1.37 (95% CI 1.28–1.46) and 1.38 (1.29–1.47), respectively. […] The risk of ICH was directly associated with diabetes duration. Compared with the group without diabetes, the DRS-adjusted HR was 1.23 (95% CI 1.12–1.35) and 1.44 (1.34–1.56) for diabetes duration ≤5 years and >5 years, respectively. The corresponding HRs with adjustment for propensity score were 1.27 (1.15–1.41) and 1.65 (1.50–1.80), respectively […] HbA1c was significantly associated with ICH among patients with diabetes: adjusted HR 1.14 (95% CI 1.10–1.17) for each 1% increase in HbA1c […] HbA1c appears to have a nonlinear J-shaped relationship with ICH (Pnonlinearity = 0.0186), with the lowest risk observed at HbA1c of 6.5% (48 mmol/mol). […] The risk of ICH among patients with HbA1c of 6.5–6.7% (48–50 mmol/mol) was comparable with the risk in patients without diabetes, suggesting that albeit having diabetes, patients with good, but not extreme, diabetes control do not appear to have excess risk of ICH compared with patients without diabetes.”

“To date, the exact mechanisms underlying the association between diabetes, HbA1c, and ICH remain unknown. […] In summary, our study suggests that diabetes is associated with increased risk of ICH that is directly associated with diabetes duration. ICH and HbA1c appear to have a J-shaped relationship, suggesting that both poor control as well as extreme intensive diabetes control might be associated with increased risk.”

…

“Mainly based on the analysis of the data from patients with type 1 diabetes, in the clinical course of diabetic kidney disease it has long been considered that an increase of albuminuria, from normoalbuminuria (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ratio [UACR] <30 mg/g) to microalbuminuria (UACR 30–299 mg/g) to macroalbuminuria (UACR ≥300 mg/g), precedes the progression of renal decline (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) (1–3). Morphological changes known as nodular glomerular sclerosis (Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodule) have also been observed in patients with diabetes and loss of renal function (4,5). Therefore, patients with diabetes and reduced renal function are deemed to have overt proteinuria with nodular glomerular sclerosis. Recently, however, cumulative evidence from several cross-sectional studies revealed that a proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes develop progression of renal decline without proteinuria (macroalbuminuria) or even without microalbuminuria, suggesting the existence of a nonproteinuric phenotype of diabetic kidney disease defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR <300 mg/g (6–11). Despite increasing attention, few clinical trials and longitudinal studies in type 2 diabetes include individuals without proteinuria or individuals with biopsy-proven diabetic kidney disease, and therefore their clinicopathological characteristics, renal prognosis, and all-cause mortality are very limited.

Similar to the U.S. and most countries in Europe, Japan has been suffering from the expanding trend in the continued increase of the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease that leads to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and high mortality (12–15). Commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development with a goal of better understanding and halting the pandemic of diabetic kidney disease, we established a nationwide biopsy-based cohort of diabetic kidney disease with followed-up data, including ESRD and death ascertainment. Using this nationwide cohort and propensity score–matching methods, we aimed to investigate clinicopathological characteristics, renal prognosis, and mortality in patients with the nonproteinuric phenotype of diabetic kidney disease compared with patients with the classical proteinuric phenotype of diabetic kidney disease.”

“This is a retrospective study of patients who underwent clinical renal biopsy performed from 1 January 1985 to 31 December 2016 and had a pathological diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease at [one of] 18 hospitals in Japan […] 895 patients underwent clinical renal biopsy and had a pathological diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease in our cohort […]. We identified 526 who had an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the time of biopsy. Among them, 88 had nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease (UACR <300 mg/g), and 438 had proteinuric diabetic kidney disease (UACR ≥300 mg/g) at baseline. After propensity score matching, the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group comprised 82 patients and the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group comprised 164 patients […] In propensity score–matched cohorts, the blood pressure in patients with nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease was better controlled compared with patients with proteinuric diabetic kidney disease, although patients with nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease were less prescribed RAAS blockade. Patients with nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease had lower total cholesterol levels and higher hemoglobin levels. For pathological characteristics, there was a difference in classification assignment for diabetic kidney disease between the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group and proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group. […] Compared with the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group, the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group had less severe interstitial and vascular lesions. […] In a multivariable logistic regression model, older age, lower systolic blood pressure, higher hemoglobin level, and higher HbA1c were significantly associated with a higher odds of nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease.”

“After a median follow-up of 1.8 years (IQR 0.9–3.7) from the date of renal biopsy, 297 (56%) of the 526 patients had renal events. The 5-year CKD progression-free survival was 33.2% (95% CI 28.4–38.2%) for all patients, 86.9% (95% CI 73.1–93.9%) for the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group, and 24.5% (95% CI 19.8–29.5%) for the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group (log-rank test P < 0.001) […]. The same trend was seen in the propensity score–matched cohort: After a median follow-up of 1.9 years (IQR 0.9–5.0) from the date of renal biopsy, 124 (50%) of the 246 matched patients had renal events. The 5-year CKD progression-free survival was 46.4% (95% CI 38.7–53.6%) for all patients, 86.6% (95% CI 72.5–93.8%) for the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group, and 30.3% (95% CI 22.4–38.6%) for the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group (log-rank test P < 0.001) […]. Similarly, for the secondary outcome (all-cause mortality), after a median follow-up of 2.7 years (IQR 1.1–5.7) from the date of renal biopsy, 55 (10%) of the 526 patients had death events. The 5-year death-free survival was 89.7% (95% CI 85.6–92.7%) for all patients, 98.4% (95% CI 89.1–99.8%) for the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group, and 87.5% (95% CI 82.5–91.2%) for the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group (log-rank test P < 0.001) […]. The same trend was seen in the propensity matched cohort: After a median follow-up of 3.1 years (IQR 1.3–7.0) from the date of renal biopsy, 35 (14%) of the 246 matched patients had death events. The 5-year death-free survival was 88.2% (95% CI 82.0–92.3%) for all patients, 98.3% (95% CI 88.7–99.8%) for the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group, and 82.6% (95% CI 73.6–88.8%) for the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group (log-rank test P = 0.005) […] The overall CKD progression incidence was significantly lower in the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group (30 [95% CI 18–50] per 1,000 person-years) than in the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group (231 [95% CI 191–278] per 1,000 person-years; crude HR 0.15 [95% CI 0.08–0.26]). After adjustment for age, sex, known duration of diabetes, and baseline eGFR, the risk of CKD progression remained lower in the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease cohort than in the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease cohort (adjusted HR 0.13 [95% CI 0.08–0.24]). The risk of CKD progression was consistently lower in the nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease group than in the proteinuric diabetic kidney disease group when stratified by potential confounders such as age, sex, obesity, retinopathy, smoking status, use of RAAS blockade, hypertension, dyslipidemia, poor glycemic control, lower eGFR, and pathological findings.”

“In conclusion, in propensity score–matched cohorts of biopsy-proven nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease and proteinuric diabetic kidney disease, patients with nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease had lower blood pressure with less frequent typical pathological lesions and were at lower risk of CKD progression and all-cause mortality. Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings in other cohorts.”

…

vi. Single herbal medicine for diabetic retinopathy (Cochrane).

“Diabetic retinopathy is one of the major causes of blindness and the number of cases has risen in recent years. Herbal medicine has been used to treat diabetes and its complications including diabetic retinopathy for thousands of years around the world. However, common practice is not always evidence‐based. Evidence is needed to help people with diabetic retinopathy or doctors to make judicious judgements about using herbal medicine as treatment.”

“We included 10 studies involving 754 participants, of which nine were conducted in China and one in Poland. In all studies, participants in both groups received conventional treatment for diabetic retinopathy which included maintaining blood glucose and lipids using medicines and keeping a stable diabetic diet. In three studies, the comparator group also received an additional potentially active comparator in the form of a vasoprotective drug. The single herbs or extracts included Ruscus extract tablet, Sanqi Tongshu capsule, tetramethylpyrazine injection, Xueshuantong injection, Puerarin injection and Xuesaitong injection. The Sanqi Tongshu capsule, Xueshuantong injection and Xuesaitong injection were all made from the extract of Radix Notoginseng (San qi) and the main ingredient was sanchinoside. The risk of bias was high in all included studies mainly due to lack of masking (blinding). None of the studies reported the primary outcome of this review, progression of retinopathy.

Combined analysis of herbal interventions suggested that people who took these herbs in combination with conventional treatment may have been more likely to gain 2 or more lines of visual acuity compared to people who did not take these herbs when compared to conventional intervention alone at the end of treatment (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.48; 5 trials, 541 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Subgroup analyses based on the different single herbs found no evidence for different effects of different herbs, but the power of this analysis was low. […]

Authors’ conclusions

No conclusions could be drawn about the effect of any single herb or herbal extract on diabetic retinopathy from the current available evidence. It was difficult to exclude the placebo effect as a possible explanation for observed differences due to the lack of placebo control in the included studies. Further adequately designed trials are needed to establish the evidence.”

Links and random stuff

i. Pulmonary Aspects of Exercise and Sports.

“Although the lungs are a critical component of exercise performance, their response to exercise and other environmental stresses is often overlooked when evaluating pulmonary performance during high workloads. Exercise can produce capillary leakage, particularly when left atrial pressure increases related to left ventricular (LV) systolic or diastolic failure. Diastolic LV dysfunction that results in elevated left atrial pressure during exercise is particularly likely to result in pulmonary edema and capillary hemorrhage. Data from race horses, endurance athletes, and triathletes support the concept that the lungs can react to exercise and immersion stress with pulmonary edema and pulmonary hemorrhage. Immersion in water by swimmers and divers can also increase stress on pulmonary capillaries and result in pulmonary edema.”

“Zavorsksy et al.11 studied individuals under several different workloads and performed lung imaging to document the presence or absence of lung edema. Radiographic image readers were blinded to the exposures and reported visual evidence of lung fluid. In individuals undergoing a diagnostic graded exercise test, no evidence of lung edema was noted. However, 15% of individuals who ran on a treadmill at 70% of maximum capacity for 2 hours demonstrated evidence of pulmonary edema, as did 65% of those who ran at maximum capacity for 7 minutes. Similar findings were noted in female athletes.12 Pingitore et al. examined 48 athletes before and after completing an iron man triathlon. They used ultrasound to detect lung edema and reported the incidence of ultrasound lung comets.13 None of the athletes had evidence of lung edema before the event, while 75% showed evidence of pulmonary edema immediately post-race, and 42% had persistent findings of pulmonary edema 12 hours post-race. Their data and several case reports14–16 have demonstrated that extreme exercise can result in pulmonary edema”

“Conclusions

Sports and recreational participation can result in lung injury caused by high pulmonary pressures and increased blood volume that raises intracapillary pressure and results in capillary rupture with subsequent pulmonary edema and hemorrhage. High-intensity exercise can result in accumulation of pulmonary fluid and evidence of pulmonary edema. Competitive swimming can result in both pulmonary edema related to fluid shifts into the thorax from immersion and elevated LV end diastolic pressure related to diastolic dysfunction, particularly in the presence of high-intensity exercise. […] The most important approach to many of these disorders is prevention. […] Prevention strategies include avoiding extreme exercise, avoiding over hydration, and assuring that inspiratory resistance is minimized.”

…

ii. Some interesting thoughts on journalism and journalists from a recent SSC Open Thread by user ‘Well’ (quotes from multiple comments). His/her thoughts seem to line up well with my own views on these topics, and one of the reasons why I don’t follow the news is that my own answer to the first question posed below is quite briefly that, ‘…well, I don’t’:

“I think a more fundamental problem is the irrational expectation that newsmedia are supposed to be a reliable source of information in the first place. Why do we grant them this make-believe power?

The English and Acting majors who got together to put on the shows in which they pose as disinterested arbiters of truth use lots of smoke and mirror techniques to appear authoritative: they open their programs with regal fanfare, they wear fancy suits, they make sure to talk or write in a way that mimics the disinterestedness of scholarly expertise, they appear with spinning globes or dozens of screens behind them as if they’re omniscient, they adorn their publications in fancy black-letter typefaces and give them names like “Sentinel” and “Observer” and “Inquirer” and “Plain Dealer”, they invented for themselves the title of “journalists” as if they take part in some kind of peer review process… But why do these silly tricks work? […] what makes the press “the press” is the little game of make-believe we play where an English or Acting major puts on a suit, talks with a funny cadence in his voice, sits in a movie set that looks like God’s Control Room, or writes in a certain format, using pseudo-academic language and symbols, and calls himself a “journalist” and we all pretend this person is somehow qualified to tell us what is going on in the world.

Even when the “journalist” is saying things we agree with, why do we participate in this ridiculous charade? […] I’m not against punditry or people putting together a platform to talk about things that happen. I’m against people with few skills other than “good storyteller” or “good writer” doing this while painting themselves as “can be trusted to tell you everything you need to know about anything”. […] Inasumuch as what I’m doing can be called “defending” them, I’d “defend” them not because they are providing us with valuable facts (ha!) but because they don’t owe us facts, or anything coherent, in the first place. It’s not like they’re some kind of official facts-providing service. They just put on clothes to look like one.”

…

iii. Chatham house rule.

…

iv. Sex Determination: Why So Many Ways of Doing It?

“Sexual reproduction is an ancient feature of life on earth, and the familiar X and Y chromosomes in humans and other model species have led to the impression that sex determination mechanisms are old and conserved. In fact, males and females are determined by diverse mechanisms that evolve rapidly in many taxa. Yet this diversity in primary sex-determining signals is coupled with conserved molecular pathways that trigger male or female development. Conflicting selection on different parts of the genome and on the two sexes may drive many of these transitions, but few systems with rapid turnover of sex determination mechanisms have been rigorously studied. Here we survey our current understanding of how and why sex determination evolves in animals and plants and identify important gaps in our knowledge that present exciting research opportunities to characterize the evolutionary forces and molecular pathways underlying the evolution of sex determination.”

…

v. So Good They Can’t Ignore You.

“Cal Newport’s 2012 book So Good They Can’t Ignore You is a career strategy book designed around four ideas.

The first idea is that ‘follow your passion’ is terrible career advice, and people who say this should be shot don’t know what they’re talking about. […] The second idea is that instead of believing in the passion hypothesis, you should adopt what Newport calls the ‘craftsman mindset’. The craftsman mindset is that you should focus on gaining rare and valuable skills, since this is what leads to good career outcomes.

The third idea is that autonomy is the most important component of a ‘dream’ job. Newport argues that when choosing between two jobs, there are compelling reasons to ‘always’ pick the one with higher autonomy over the one with lower autonomy.

The fourth idea is that having a ‘mission’ or a ‘higher purpose’ in your job is probably a good idea, and is really nice if you can find it. […] the book structure is basically: ‘following your passion is bad, instead go for Mastery[,] Autonomy and Purpose — the trio of things that have been proven to motivate knowledge workers’.” […]

“Newport argues that applying deliberate practice to your chosen skill market is your best shot at becoming ‘so good they can’t ignore you’. The key is to stretch — you want to practice skills that are just above your current skill level, so that you experience discomfort — but not too much discomfort that you’ll give up.” […]

“Newport thinks that if your job has one or more of the following qualities, you should leave your job in favour of another where you can build career capital:

- Your job presents few opportunities to distinguish yourself by developing relevant skills that are rare and valuable.

- Your job focuses on something you think is useless or perhaps even actively bad for the world.

- Your job forces you to work with people you really dislike.

If you’re in a job with any of these traits, your ability to gain rare and valuable skills would be hampered. So it’s best to get out.”

…

vi. Structural brain imaging correlates of general intelligence in UK Biobank.

“The association between brain volume and intelligence has been one of the most regularly-studied—though still controversial—questions in cognitive neuroscience research. The conclusion of multiple previous meta-analyses is that the relation between these two quantities is positive and highly replicable, though modest (Gignac & Bates, 2017; McDaniel, 2005; Pietschnig, Penke, Wicherts, Zeiler, & Voracek, 2015), yet its magnitude remains the subject of debate. The most recent meta-analysis, which included a total sample size of 8036 participants with measures of both brain volume and intelligence, estimated the correlation at r = 0.24 (Pietschnig et al., 2015). A more recent re-analysis of the meta-analytic data, only including healthy adult samples (N = 1758), found a correlation of r = 0.31 (Gignac & Bates, 2017). Furthermore, the correlation increased as a function of intelligence measurement quality: studies with better-quality intelligence tests—for instance, those including multiple measures and a longer testing time—tended to produce even higher correlations with brain volume (up to 0.39). […] Here, we report an analysis of data from a large, single sample with high-quality MRI measurements and four diverse cognitive tests. […] We judge that the large N, study homogeneity, and diversity of cognitive tests relative to previous large scale analyses provides important new evidence on the size of the brain structure-intelligence correlation. By investigating the relations between general intelligence and characteristics of many specific regions and subregions of the brain in this large single sample, we substantially exceed the scope of previous meta-analytic work in this area. […]

“We used a large sample from UK Biobank (N = 29,004, age range = 44–81 years). […] This preregistered study provides a large single sample analysis of the global and regional brain correlates of a latent factor of general intelligence. Our study design avoids issues of publication bias and inconsistent cognitive measurement to which meta-analyses are susceptible, and also provides a latent measure of intelligence which compares favourably with previous single-indicator studies of this type. We estimate the correlation between total brain volume and intelligence to be r = 0.276, which applies to both males and females. Multiple global tissue measures account for around double the variance in g in older participants, relative to those in middle age. Finally, we find that associations with intelligence were strongest in frontal, insula, anterior and medial temporal, lateral occipital and paracingulate cortices, alongside subcortical volumes (especially the thalamus) and the microstructure of the thalamic radiations, association pathways and forceps minor.”

…

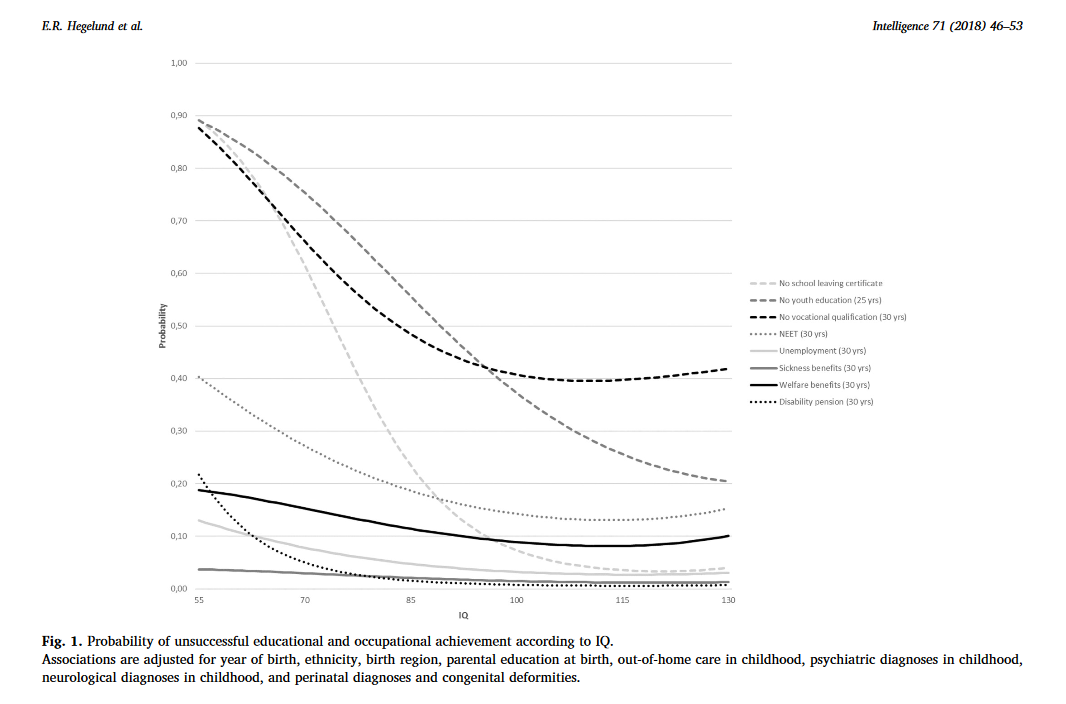

vii. Another IQ study: Low IQ as a predictor of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement: A register-based study of 1,098,742 men in Denmark 1968–2016.

“Intelligence test score is a well-established predictor of educational and occupational achievement worldwide […]. Longitudinal studies typically report cor-relation coefficients of 0.5–0.6 between intelligence and educational achievement as assessed by educational level or school grades […], correlation coefficients of 0.4–0.5 between intelligence and occupational level […] and cor-relation coefficients of 0.2–0.4 between intelligence and income […]. Although the above-mentioned associations are well-established, low intelligence still seems to be an overlooked problem among young people struggling to complete an education or gain a foothold in the labour market […] Due to contextual differences with regard to educational system and flexibility and security on the labour market as well as educational and labour market policies, the role of intelligence in predicting unsuccessful educational and occupational courses may vary among countries. As Denmark has free admittance to education at all levels, state financed student grants for all students, and a relatively high support of students with special educational needs, intelligence might be expected to play a larger role – as socioeconomic factors might be of less importance – with regard to educational and occupational achievement compared with countries outside Scandinavia. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the role of IQ in predicting a wide range of indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement among young people born across five decades in Denmark.”

“Individuals who differed in IQ score were found to differ with regard to all indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement such that low IQ was associated with a higher proportion of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement. For example, among the 12.1% of our study population who left lower secondary school without receiving a certificate, 39.7% had an IQ < 80 and 23.1% had an IQ of 80–89, although these individuals only accounted for 7.8% and 13.1% of the total study population. The main analyses showed that IQ was inversely associated with all indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement in young adulthood after adjustment for covariates […] With regard to unsuccessful educational achievement, […] the probabilities of no school leaving certificate, no youth education at age 25, and no vocational qualification at age 30 decreased with increasing IQ in a cubic relation, suggesting essentially no or only weak associations at superior IQ levels. IQ had the strongest influence on the probability of no school leaving certificate. Although the probabilities of the three outcome indicators were almost the same among individuals with extremely low IQ, the probability of no school leaving certificate approached zero among individuals with an IQ of 100 or above whereas the probabilities of no youth education at age 25 and no vocational qualification at age 30 remained notably higher. […] individuals with an IQ of 70 had a median gross income of 301,347 DKK, individuals with an IQ of 100 had a median gross income of 331,854, and individuals with an IQ of 130 had a median gross income of 363,089 DKK – in the beginning of June 2018 corresponding to about 47,856 USD, 52,701 USD, and 57,662 USD, respectively. […] The results showed that among individuals undergoing education, low IQ was associated with a higher hazard rate of passing to employment, unemployment, sickness benefits receipt and welfare benefits receipt […]. This indicates that individuals with low IQ tend to leave the educational system to find employment at a younger age than individuals with high IQ, but that this early leave from the educational system often is associated with a transition into unemployment, sickness benefits receipt and welfare benefits receipt.”

“Conclusions

This study of 1,098,742 Danish men followed in national registers from 1968 to 2016 found that low IQ was a strong and consistent predictor of 10 indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement in young adulthood. Overall, it seemed that IQ had the strongest influence on the risk of unsuccessful educational achievement and on the risk of disability pension, and that the influence of IQ on educational achievement was strongest in the early educational career and decreased over time. At the community level our findings suggest that intelligence should be considered when planning interventions to reduce the rates of early school leaving and the unemployment rates and at the individual level our findings suggest that assessment of intelligence may provide crucial information for the counselling of poor-functioning schoolchildren and adolescents with regard to both the immediate educational goals and the more distant work-related future.”

A few diabetes papers of interest

Some observations from the paper:

“Type 1 diabetes is preceded by the presence of preclinical, persistent islet autoantibodies (1). Autoantibodies against insulin (IAA) (2), GAD (GADA), insulinoma-associated antigen 2 (IA-2A) (3), and/or zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8A) (4) are typically present prior to development of symptomatic hyperglycemia and progression to clinical disease. These autoantibodies may develop many years before onset of type 1 diabetes, and increasing autoantibody number and titers have been associated with increased risk of progression to disease (5–7).

Identical twins have an increased risk of progression of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes after one twin is diagnosed, although reported rates have been highly variable (30–70%) (8–11). This risk is increased if the proband twin develops diabetes at a young age (12). Concordance rates for type 1 diabetes in monozygotic twins with long-term follow-up is >50% (13). Risk for development of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes for nonidentical twins is thought to be similar to non-twin siblings (risk of 6–10% for diabetes) (14). Full siblings who inherit both high-risk HLA (HLA DQA1*05:01 DR3/4*0302) haplotypes identical to their proband sibling with type 1 diabetes have a much higher risk for development of diabetes than those who share only one or zero haplotypes (55% vs. 5% by 12 years of age, respectively; P = 0.03) (15). Despite sharing both HLA haplotypes with their proband, siblings without the HLA DQA1*05:01 DR3/4*0302 genotype had only a 25% risk for type 1 diabetes by 12 years of age (15).”

“The TrialNet Pathway to Prevention Study (previously the TrialNet Natural History Study; 16) has been screening relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes since 2004 and follows these subjects with serial autoantibody testing for the development of islet autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes. The study offers longitudinal monitoring for autoantibody-positive subjects through HbA1c testing and oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs).”

“The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of islet autoantibodies and analyze a logistic regression model to test the effects of genetic factors and common twin environment on the presence or absence of islet autoantibodies in identical twins, nonidentical twins, and full siblings screened in the TrialNet Pathway to Prevention Study. In addition, this study analyzed the presence of islet autoantibodies (GADA, IA-2A, and IAA) and risk of type 1 diabetes over time in identical twins, nonidentical twins, and full siblings followed in the TrialNet Pathway to Prevention Study. […] A total of 48,051 sibling subjects were initially screened (288 identical twins, 630 nonidentical twins, and 47,133 full siblings). Of these, 48,026 had an initial screening visit with GADA, IA2A, and IAA results (287 identical twins, 630 nonidentical twins, and 47,109 full siblings). A total of 17,226 participants (157 identical twins, 283 nonidentical twins and 16,786 full siblings) were followed for a median of 2.1 years (25th percentile 1.1 year and 75th percentile 4.0 years), with follow-up defined as at least ≥12 months follow-up after initial screening visit.”

“At the initial screening visit, GADA was present in 20.2% of identical twins (58 out of 287), 5.6% of nonidentical twins (35 out of 630), and 4.7% of full siblings (2,205 out of 47,109) (P < 0.0001). Additionally, IA-2A was present primarily in identical twins (9.4%; 27 out of 287) and less so in nonidentical twins (3.3%; 21 out of 630) and full siblings (2.2%; 1,042 out of 47,109) (P = 0.0001). Nearly 12% of identical twins (34 out of 287) were positive for IAA at initial screen, whereas 4.6% of nonidentical twins (29 out of 630) and 2.5% of full siblings (1,152 out of 47,109) were initially IAA positive (P < 0.0001).”

“At 3 years of follow-up, the risk for development of GADA was 16% for identical twins, 5% for nonidentical twins, and 4% for full siblings (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). The risk for development of IA-2A by 3 years of follow-up was 7% for identical twins, 4% for nonidentical twins, and 2% for full siblings (P = 0.0005) (Fig. 1B). At 3 years of follow-up, the risk of development of IAA was 10% for identical twins, 5% for nonidentical twins, and 4% for full siblings (P = 0.006) […] In initially autoantibody-negative subjects, 1.5% of identical twins, 0% of nonidentical twins, and 0.5% of full siblings progressed to diabetes at 3 years of follow-up (P = 0.18) […] For initially single autoantibody–positive subjects, at 3 years of follow-up, 69% of identical twins, 13% of nonidentical twins, and 12% of full siblings developed type 1 diabetes (P < 0.0001) […] Subjects who were positive for multiple autoantibodies at screening had a higher risk of developing type 1 diabetes at 3 years of follow-up with 69% of identical twins, 72% of nonidentical twins, and 47% of full siblings developing type 1 diabetes (P = 0.079)”

“Because TrialNet is not a birth cohort and the median age at screening visit was 11 years overall, this study would not capture subjects who had initial seroconversion at a young age and then progressed through the intermediate stage of multiple antibody positivity before developing diabetes.”

“This study of >48,000 siblings of patients with type 1 diabetes shows that at initial screening, identical twins were more likely to have at least one positive autoantibody and be positive for GADA, IA-2A, and IAA than either nonidentical twins or full siblings. […] risk for development of type 1 diabetes at 3 years of follow-up was high for both single and multiple autoantibody–positive identical twins (62–69%) and multiple autoantibody–positive nonidentical twins (72%) compared with 47% for initially multiple autoantibody–positive full siblings and 12–13% for initially single autoantibody–positive nonidentical twins and full siblings. To our knowledge, this is the largest prediagnosis study to evaluate the effects of genetic factors and common twin environment on the presence or absence of islet autoantibodies.

In this study, younger age, male sex, and genetic factors were significantly associated with expression of IA-2A, IAA, more than one autoantibody, and more than two autoantibodies, whereas only genetic factors were significant for GADA. An influence of common twin environment (E) was not seen. […] Previous studies have shown that identical twin siblings of patients with type 1 diabetes have a higher concordance rate for development of type 1 diabetes compared with nonidentical twins, although reported rates for identical twins have been highly variable (30–70%) […]. Studies from various countries (Australia, Denmark, Finland, Great Britain, and U.S.) have reported concordance rates for nonidentical twins ∼5–15% […]. Concordance rates have been higher when the proband was diagnosed at a younger age (8), which may explain the variability in these reported rates. In this study, autoantibody-negative nonidentical and identical twins had a low risk of type 1 diabetes by 3 years of follow-up. In contrast, once twins developed autoantibodies, risk for type 1 diabetes was high for multiple autoantibody nonidentical twins and both single and multiple autoantibody identical twins.”

…

This is another paper in the ‘‘ segment from the February edition of Diabetes Care – multiple other papers on related topics were also included in that edition, so if you’re interested in the genetics of diabetes it may be worth checking out.

Some observations from the paper:

“Type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease due to a gradual reduction in the capacity of the pancreatic islet cells (β-cells) to produce insulin (1). The clinical course of this progression is highly variable, with some patients progressing very rapidly to requiring insulin treatment, whereas others can be successfully treated with lifestyle changes or oral agents for many years (1,2). Being able to identify patients likely to rapidly progress may have clinical utility in prioritization monitoring and treatment escalation and in choice of therapy.

It has previously been shown that many patients with clinical features of type 2 diabetes have positive GAD65 autoantibodies (GADA) and that the presence of this autoantibody is associated with faster progression to insulin (3,4). This is often termed latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) (5,6). However, the predictive value of GADA testing is limited in a population with clinical type 2 diabetes, with many GADA-positive patients not requiring insulin treatment for many years (4,7). Previous research has suggested that genetic variants in the HLA region associated with type 1 diabetes are associated with more rapid progression to insulin in patients with clinically defined type 2 diabetes and positive GADA (8).

We have recently developed a type 1 diabetes genetic risk score (T1D GRS), which provides an inexpensive ($70 in our local clinical laboratory and <$20 where DNA has been previously extracted), integrated assessment of a person’s genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes (9). The score is composed of 30 type 1 diabetes risk variants weighted for effect size and aids discrimination of type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes. […] We aimed to determine if the T1D GRS could predict rapid progression to insulin (within 5 years of diagnosis) over and above GADA testing in patients with a clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes treated without insulin at diagnosis.”

“We examined the relationship between GADA, T1D GRS, and progression to insulin therapy using survival analysis in 8,608 participants with clinical type 2 diabetes initially treated without insulin therapy. […] In this large study of participants with a clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, we have found that type 1 genetic susceptibility alters the clinical implications of a positive GADA when predicting rapid time to insulin. GADA-positive participants with high T1D GRS were more likely to require insulin within 5 years of diagnosis, with 48% progressing to insulin in this time in contrast to only 18% in participants with low T1D GRS. The T1D GRS was independent of and additive to participant’s age of diagnosis and BMI. However, T1D GRS was not associated with rapid insulin requirement in participants who were GADA negative.”

“Our findings have clear implications for clinical practice. The T1D GRS represents a novel clinical test that can be used to enhance the prognostic value of GADA testing. For predicting future insulin requirement in patients with apparent type 2 diabetes who are GADA positive, T1D GRS may be clinically useful and can be used as an additional test in the screening process. However, in patients with type 2 diabetes who are GADA negative, there is no benefit gained from genetic testing. This is unsurprising, as the prevalence of underlying autoimmunity in patients with a clinical phenotype of type 2 diabetes who are GADA negative is likely to be extremely low; therefore, most GADA-negative participants with high T1D GRS will have nonautoimmune diabetes. The use of this two-step testing approach may facilitate a precision medicine approach to patients with apparent type 2 diabetes; patients who are likely to progress rapidly are identified for targeted management, which may include increased monitoring, early therapy intensification, and/or interventions aimed at slowing progression (36,37).

The costs of analyzing the T1D GRS are relatively modest and may fall further, as genetic testing is rapidly becoming less expensive (38). […] In conclusion, a T1D GRS alters the clinical implications of a positive GADA test in patients with clinical type 2 diabetes and is independent of and additive to clinical features. This therefore represents a novel test for identifying patients with rapid progression in this population.”

…

iii. Retinopathy and RAAS Activation: Results From the Canadian Study of Longevity in Type 1 Diabetes.

“Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of preventable blindness in individuals ages 20–74 years and is the most common vascular complication in type 1 and type 2 diabetes (1–3). On the basis of increasing severity, diabetic retinopathy is classified into nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), defined in early stages by the presence of microaneurysms, retinal vascular closure, and alteration, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), defined by the growth of new aberrant blood vessels (neovascularization) susceptible to hemorrhage, leakage, and fibrosis (4). Diabetic macular edema (DME) can be present at any stage of retinopathy and is characterized by increased vascular permeability leading to retinal thickening.

Important risk factors for the development of retinopathy continue to be chronic hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes duration (5,6). Given the systemic nature of these risk factors, cooccurrence of retinopathy with other vascular complications is common in patients with diabetes.”

“A key pathway implicated in diabetes-related small-vessel disease is overactivation of neurohormones. Activation of the neurohormonal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway predominates in diabetes in response to hyperglycemia and sodium retention. The RAAS plays a pivotal role in regulating systemic BP through vasoconstriction and fluid-electrolyte homeostasis. At the tissue level, angiotensin II (ANGII), the principal mediator of the RAAS, is implicated in fibrosis, oxidative stress, endothelial damage, thrombosis, inflammation, and vascular remodeling. Of note, systemic RAAS blockers reduce the risk of progression of eye disease but not DKD [Diabetic Kidney Disease, US] in adults with type 1 diabetes with normoalbuminuria (12).

Several longitudinal epidemiologic studies of diabetic retinopathy have been completed in type 1 diabetes; however, few have studied the relationships between eye, nerve, and renal complications and the influence of RAAS activation after prolonged duration (≥50 years) in adults with type 1 diabetes. As a result, less is known about mechanisms that persist in diabetes-related microvascular complications after long-standing diabetes. Accordingly, in this cross-sectional analysis from the Canadian Study of Longevity in Type 1 Diabetes involving adults with type 1 diabetes for ≥50 years, our aims were to phenotype retinopathy stage and determine associations between the presence of retinopathy and other vascular complications. In addition, we examined the relationship between retinopathy stage and renal and systemic hemodynamic function, including arterial stiffness, at baseline and dynamically after RAAS activation with an infusion of exogenous ANGII.”

“Of the 75 participants, 12 (16%) had NDR [no diabetic retinopathy], 24 (32%) had NPDR, and 39 (52%) had PDR […]. At baseline, those with NDR had lower mean HbA1c compared with those with NPDR and PDR (7.4 ± 0.7% and 7.5 ± 0.9%, respectively; P for trend = 0.019). Of note, those with more severe eye disease (PDR) had lower systolic and diastolic BP values but a significantly higher urine albumin-to-creatine ratio (UACR) […] compared with those with less severe eye disease (NPDR) or with NDR despite higher use of RAAS inhibitors among those with PDR compared with NPDR or NDR. History of cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease history was significantly higher in participants with PDR (33.3%) than in those with NPDR (8.3%) or NDR (0%). Diabetic sensory polyneuropathy was prevalent across all groups irrespective of retinopathy status but was numerically higher in the PDR group (95%) than in the NPDR (86%) or NDR (75%) groups. No significant differences were observed in retinal thickness across the three groups.”

One quick note: This was mainly an eye study, but some of the other figures here are well worth taking note of. 3 out of 4 people in the supposedly low-risk group without eye complications had sensory polyneuropathy after 50 years of diabetes.

“Conclusions

Hyperglycemia contributes to the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy through multiple interactive pathways, including increased production of advanced glycation end products, IGF-I, vascular endothelial growth factor, endothelin, nitric oxide, oxidative damage, and proinflammatory cytokines (29–33). Overactivation of the RAAS in response to hyperglycemia also is implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes-related complications in the retina, nerves, and kidney and is an important therapeutic target in type 1 diabetes. Despite what is known about these underlying pathogenic mechanisms in the early development of diabetes-related complications, whether the same mechanisms are active in the setting of long-standing type 1 diabetes is not known. […] In this study, we observed that participants with PDR were more likely to be taking RAAS inhibitors, to have a higher frequency of cardiovascular or peripheral vascular disease, and to have higher UACR levels, likely reflecting the higher overall risk profile of this group. Although it is not possible to determine why some patients in this cohort developed PDR while others did not after similar durations of type 1 diabetes, it seems unlikely that glycemic control alone is sufficient to fully explain the observed between-group differences and differing vascular risk profiles. Whereas the NDR group had significantly lower mean HbA1c levels than the NPDR and PDR groups, differences between participants with NPDR and those with PDR were modest. Accordingly, other factors, such as differences in vascular function, neurohormones, growth factors, genetics, and lifestyle, may play a role in determining retinopathy severity at the individual level.

The association between retinopathy and risk for DKD is well established in diabetes (34). In the setting of type 2 diabetes, patients with high levels of UACR have twice the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy than those with normal UACR levels. For example, Rodríguez-Poncelas et al. (35) demonstrated that impaired renal function is linked with increased diabetic retinopathy risk. Consistent with these studies and others, the PDR group in this Canadian Study of Longevity in Type 1 Diabetes demonstrated significantly higher UACR, which is associated with an increased risk of DKD progression, illustrating that the interaction between eye and kidney disease progression also may exist in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes. […] In conclusion, retinopathy was prevalent after prolonged type 1 diabetes duration, and retinopathy severity associated with several measures of neuropathy and with higher UACR. Differential exaggerated responses to RAAS activation in the peripheral vasculature of the PDR group highlights that even in the absence of DKD, neurohormonal abnormalities are likely still operant, and perhaps accentuated, in patients with PDR even after long-standing type 1 diabetes duration.”

…

iv. Clinical and MRI Features of Cerebral Small-Vessel Disease in Type 1 Diabetes.

“Type 1 diabetes is associated with a fivefold increased risk of stroke (1), with cerebral small-vessel disease (SVD) as the most common etiology (2). Cerebral SVD in type 1 diabetes, however, remains scarcely investigated and is challenging to study in vivo per se owing to the size of affected vasculature (3); instead, MRI signs of SVD are studied. In this study, we aimed to assess the prevalence of cerebral SVD in subjects with type 1 diabetes compared with healthy control subjects and to characterize diabetes-related variables associated with SVD in stroke-free people with type 1 diabetes.”

“RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS This substudy was cross-sectional in design and included 191 participants with type 1 diabetes and median age 40.0 years (interquartile range 33.0–45.1) and 30 healthy age- and sex-matched control subjects. All participants underwent clinical investigation and brain MRIs, assessed for cerebral SVD.

RESULTS Cerebral SVD was more common in participants with type 1 diabetes than in healthy control subjects: any marker 35% vs. 10% (P = 0.005), cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) 24% vs. 3.3% (P = 0.008), white matter hyperintensities 17% vs. 6.7% (P = 0.182), and lacunes 2.1% vs. 0% (P = 1.000). Presence of CMBs was independently associated with systolic blood pressure (odds ratio 1.03 [95% CI 1.00–1.05], P = 0.035).”

“Conclusions

Cerebral SVD is more common in participants with type 1 diabetes than in healthy control subjects. CMBs especially are more prevalent and are independently associated with hypertension. Our results indicate that cerebral SVD starts early in type 1 diabetes but is not explained solely by diabetes-related vascular risk factors or the generalized microvascular disease that takes place in diabetes (7).

There are only small-scale studies on cerebral SVD, especially CMBs, in type 1 diabetes. Compared with the current study, one study with similar diabetes characteristics (i.e., diabetes duration, glycemic control, and blood pressure levels) as in the current study, but lacking a control population, showed a higher prevalence of WMHs, with more than half of the participants affected, but similar prevalence of lacunes and lower prevalence of CMBs (8). In another study, including 67 participants with type 1 diabetes and 33 control subjects, there was no difference in WMH prevalence but a higher prevalence of CMBs in participants with type 1 diabetes and retinopathy compared with control subjects (9). […] In type 1 diabetes, albuminuria and systolic blood pressure independently increase the risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (12). […] We conclude that cerebral SVD is more common in subjects with type 1 diabetes than in healthy control subjects. Future studies will focus on longitudinal development of SVD in type 1 diabetes and the associations with brain health and cognition.”

…

“In the U.S., an estimated 1.4 million adults are newly diagnosed with diabetes every year and present an important intervention opportunity for health care systems. In patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the benefits of maintaining an HbA1c <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) are well established. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) found that a mean HbA1c of 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) lowers the risk of diabetes-related end points by 12–32% compared with a mean HbA1c of 7.9% (63 mmol/mol) (1,2). Long-term observational follow-up of this trial revealed that this early glycemic control has durable effects: Reductions in microvascular events persisted, reductions in cardiovascular events and mortality were observed 10 years after the trial ended, and HbA1c values converged (1). Similar findings were observed in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) in patients with type 1 diabetes (2–4). These posttrial observations have been called legacy effects (also metabolic memory) (5), and they suggest the importance of early glycemic control for the prevention of future complications of diabetes. Although these clinical trial long-term follow-up studies demonstrated legacy effects, whether legacy effects exist in real-world populations, how soon after diabetes diagnosis legacy effects may begin, or for what level of glycemic control legacy effects may exist are not known.

In a previous retrospective cohort study, we found that patients with newly diagnosed diabetes and an initial 10-year HbA1c trajectory that was unstable (i.e., changed substantially over time) had an increased risk for future microvascular events, even after adjusting for HbA1c exposure (6). In the same cohort population, this study evaluates associations between the duration and intensity of glycemic control immediately after diagnosis and the long-term incidence of future diabetic complications and mortality. We hypothesized that a glycemic legacy effect exists in real-world populations, begins as early as the 1st year after diabetes diagnosis, and depends on the level of glycemic exposure.”

“RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS This cohort study of managed care patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and 10 years of survival (1997–2013, average follow-up 13.0 years, N = 34,737) examined associations between HbA1c <6.5% (<48 mmol/mol), 6.5% to <7.0% (48 to <53 mmol/mol), 7.0% to <8.0% (53 to <64 mmol/mol), 8.0% to <9.0% (64 to <75 mmol/mol), or ≥9.0% (≥75 mmol/mol) for various periods of early exposure (0–1, 0–2, 0–3, 0–4, 0–5, 0–6, and 0–7 years) and incident future microvascular (end-stage renal disease, advanced eye disease, amputation) and macrovascular (stroke, heart disease/failure, vascular disease) events and death, adjusting for demographics, risk factors, comorbidities, and later HbA1c.

RESULTS Compared with HbA1c <6.5% (<48 mmol/mol) for the 0-to-1-year early exposure period, HbA1c levels ≥6.5% (≥48 mmol/mol) were associated with increased microvascular and macrovascular events (e.g., HbA1c 6.5% to <7.0% [48 to <53 mmol/mol] microvascular: hazard ratio 1.204 [95% CI 1.063–1.365]), and HbA1c levels ≥7.0% (≥53 mmol/mol) were associated with increased mortality (e.g., HbA1c 7.0% to <8.0% [53 to <64 mmol/mol]: 1.290 [1.104–1.507]). Longer periods of exposure to HbA1c levels ≥8.0% (≥64 mmol/mol) were associated with increasing microvascular event and mortality risk.

CONCLUSIONS Among patients with newly diagnosed diabetes and 10 years of survival, HbA1c levels ≥6.5% (≥48 mmol/mol) for the 1st year after diagnosis were associated with worse outcomes. Immediate, intensive treatment for newly diagnosed patients may be necessary to avoid irremediable long-term risk for diabetic complications and mortality.”

Do note that the effect sizes here are very large and this stuff seems really quite important. Judging from the results of this study, if you’re newly diagnosed and you only obtain a HbA1c of say, 7.3% in the first year, that may translate into a close to 30% increased risk of death more than 10 years into the future, compared to a scenario of an HbA1c of 6.3%. People who did not get their HbA1c measured within the first 3 months after diagnosis had a more than 20% increased risk of mortality during the study period. This seems like critical stuff to get right.

…

“Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a life-threatening complication of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) that results from absolute insulin deficiency and is marked by acidosis, ketosis, and hyperglycemia (1). Therefore, prevention of DKA is one goal in T1DM care, but recent data indicate increased incidence (2).

For adult patients, only limited data are available on rates and risk factors for development of DKA, and this complication remains epidemiologically poorly characterized. The Diabetes Prospective Follow-up Registry (DPV) has followed patients with diabetes from 1995. Data for this study were collected from 2000 to 2016. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of T1DM, age at diabetes onset ≥6 months, patient age at follow-up ≥18 years, and diabetes duration ≥1 year to exclude DKA at manifestation. […] In total, 46,966 patients were included in this study (average age 38.5 years [median 21.2], 47.6% female). The median HbA1c was 7.7% (61 mmol/mol), median diabetes duration was 13.6 years, and 58.3% of the patients were treated in large diabetes centers.

On average, 2.5 DKA-related hospital admissions per 100 patient-years (PY) were observed (95% CI 2.1–3.0). The rate was highest in patients aged 18–30 years (4.03/100 PY) and gradually declined with increasing age […] No significant differences between males (2.46/100 PY) and females (2.59/100 PY) were found […] Patients with HbA1c levels <7% (53 mmol/mol) had significantly fewer DKA admissions than patients with HbA1c ≥9% (75 mmol/mol) (0.88/100 PY vs. 6.04/100 PY; P < 0.001)”

“Regarding therapy, use of an insulin pump (continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion [CSII]) was not associated with higher DKA rates […], while patients aged 31–50 years on CSII showed lower rates than patients using multiple daily injections (2.21 vs. 3.12/100 PY; adjusted P < 0.05) […]. Treatment in a large center was associated with lower DKA-related hospital admissions […] In both adults and children, poor metabolic control was the strongest predictor of hospital admission due to DKA. […] In conclusion, the results of this study identify patients with T1DM at risk for DKA (high HbA1c, diabetes duration 5–10 years, migrants, age 30 years and younger) in real-life diabetes care. These at-risk individuals may need specific attention since structured diabetes education has been demonstrated to specifically reduce and prevent this acute complication.”

Viruses

This book is not great, but it’s also not bad – I ended up giving it three stars on goodreads, being much closer to 2 stars than 4. It’s a decent introduction to the field of virology, but not more than that. Below some quotes and links related to the book’s coverage.

…