Links and random stuff

i. Pulmonary Aspects of Exercise and Sports.

“Although the lungs are a critical component of exercise performance, their response to exercise and other environmental stresses is often overlooked when evaluating pulmonary performance during high workloads. Exercise can produce capillary leakage, particularly when left atrial pressure increases related to left ventricular (LV) systolic or diastolic failure. Diastolic LV dysfunction that results in elevated left atrial pressure during exercise is particularly likely to result in pulmonary edema and capillary hemorrhage. Data from race horses, endurance athletes, and triathletes support the concept that the lungs can react to exercise and immersion stress with pulmonary edema and pulmonary hemorrhage. Immersion in water by swimmers and divers can also increase stress on pulmonary capillaries and result in pulmonary edema.”

“Zavorsksy et al.11 studied individuals under several different workloads and performed lung imaging to document the presence or absence of lung edema. Radiographic image readers were blinded to the exposures and reported visual evidence of lung fluid. In individuals undergoing a diagnostic graded exercise test, no evidence of lung edema was noted. However, 15% of individuals who ran on a treadmill at 70% of maximum capacity for 2 hours demonstrated evidence of pulmonary edema, as did 65% of those who ran at maximum capacity for 7 minutes. Similar findings were noted in female athletes.12 Pingitore et al. examined 48 athletes before and after completing an iron man triathlon. They used ultrasound to detect lung edema and reported the incidence of ultrasound lung comets.13 None of the athletes had evidence of lung edema before the event, while 75% showed evidence of pulmonary edema immediately post-race, and 42% had persistent findings of pulmonary edema 12 hours post-race. Their data and several case reports14–16 have demonstrated that extreme exercise can result in pulmonary edema”

“Conclusions

Sports and recreational participation can result in lung injury caused by high pulmonary pressures and increased blood volume that raises intracapillary pressure and results in capillary rupture with subsequent pulmonary edema and hemorrhage. High-intensity exercise can result in accumulation of pulmonary fluid and evidence of pulmonary edema. Competitive swimming can result in both pulmonary edema related to fluid shifts into the thorax from immersion and elevated LV end diastolic pressure related to diastolic dysfunction, particularly in the presence of high-intensity exercise. […] The most important approach to many of these disorders is prevention. […] Prevention strategies include avoiding extreme exercise, avoiding over hydration, and assuring that inspiratory resistance is minimized.”

…

ii. Some interesting thoughts on journalism and journalists from a recent SSC Open Thread by user ‘Well’ (quotes from multiple comments). His/her thoughts seem to line up well with my own views on these topics, and one of the reasons why I don’t follow the news is that my own answer to the first question posed below is quite briefly that, ‘…well, I don’t’:

“I think a more fundamental problem is the irrational expectation that newsmedia are supposed to be a reliable source of information in the first place. Why do we grant them this make-believe power?

The English and Acting majors who got together to put on the shows in which they pose as disinterested arbiters of truth use lots of smoke and mirror techniques to appear authoritative: they open their programs with regal fanfare, they wear fancy suits, they make sure to talk or write in a way that mimics the disinterestedness of scholarly expertise, they appear with spinning globes or dozens of screens behind them as if they’re omniscient, they adorn their publications in fancy black-letter typefaces and give them names like “Sentinel” and “Observer” and “Inquirer” and “Plain Dealer”, they invented for themselves the title of “journalists” as if they take part in some kind of peer review process… But why do these silly tricks work? […] what makes the press “the press” is the little game of make-believe we play where an English or Acting major puts on a suit, talks with a funny cadence in his voice, sits in a movie set that looks like God’s Control Room, or writes in a certain format, using pseudo-academic language and symbols, and calls himself a “journalist” and we all pretend this person is somehow qualified to tell us what is going on in the world.

Even when the “journalist” is saying things we agree with, why do we participate in this ridiculous charade? […] I’m not against punditry or people putting together a platform to talk about things that happen. I’m against people with few skills other than “good storyteller” or “good writer” doing this while painting themselves as “can be trusted to tell you everything you need to know about anything”. […] Inasumuch as what I’m doing can be called “defending” them, I’d “defend” them not because they are providing us with valuable facts (ha!) but because they don’t owe us facts, or anything coherent, in the first place. It’s not like they’re some kind of official facts-providing service. They just put on clothes to look like one.”

…

iii. Chatham house rule.

…

iv. Sex Determination: Why So Many Ways of Doing It?

“Sexual reproduction is an ancient feature of life on earth, and the familiar X and Y chromosomes in humans and other model species have led to the impression that sex determination mechanisms are old and conserved. In fact, males and females are determined by diverse mechanisms that evolve rapidly in many taxa. Yet this diversity in primary sex-determining signals is coupled with conserved molecular pathways that trigger male or female development. Conflicting selection on different parts of the genome and on the two sexes may drive many of these transitions, but few systems with rapid turnover of sex determination mechanisms have been rigorously studied. Here we survey our current understanding of how and why sex determination evolves in animals and plants and identify important gaps in our knowledge that present exciting research opportunities to characterize the evolutionary forces and molecular pathways underlying the evolution of sex determination.”

…

v. So Good They Can’t Ignore You.

“Cal Newport’s 2012 book So Good They Can’t Ignore You is a career strategy book designed around four ideas.

The first idea is that ‘follow your passion’ is terrible career advice, and people who say this should be shot don’t know what they’re talking about. […] The second idea is that instead of believing in the passion hypothesis, you should adopt what Newport calls the ‘craftsman mindset’. The craftsman mindset is that you should focus on gaining rare and valuable skills, since this is what leads to good career outcomes.

The third idea is that autonomy is the most important component of a ‘dream’ job. Newport argues that when choosing between two jobs, there are compelling reasons to ‘always’ pick the one with higher autonomy over the one with lower autonomy.

The fourth idea is that having a ‘mission’ or a ‘higher purpose’ in your job is probably a good idea, and is really nice if you can find it. […] the book structure is basically: ‘following your passion is bad, instead go for Mastery[,] Autonomy and Purpose — the trio of things that have been proven to motivate knowledge workers’.” […]

“Newport argues that applying deliberate practice to your chosen skill market is your best shot at becoming ‘so good they can’t ignore you’. The key is to stretch — you want to practice skills that are just above your current skill level, so that you experience discomfort — but not too much discomfort that you’ll give up.” […]

“Newport thinks that if your job has one or more of the following qualities, you should leave your job in favour of another where you can build career capital:

- Your job presents few opportunities to distinguish yourself by developing relevant skills that are rare and valuable.

- Your job focuses on something you think is useless or perhaps even actively bad for the world.

- Your job forces you to work with people you really dislike.

If you’re in a job with any of these traits, your ability to gain rare and valuable skills would be hampered. So it’s best to get out.”

…

vi. Structural brain imaging correlates of general intelligence in UK Biobank.

“The association between brain volume and intelligence has been one of the most regularly-studied—though still controversial—questions in cognitive neuroscience research. The conclusion of multiple previous meta-analyses is that the relation between these two quantities is positive and highly replicable, though modest (Gignac & Bates, 2017; McDaniel, 2005; Pietschnig, Penke, Wicherts, Zeiler, & Voracek, 2015), yet its magnitude remains the subject of debate. The most recent meta-analysis, which included a total sample size of 8036 participants with measures of both brain volume and intelligence, estimated the correlation at r = 0.24 (Pietschnig et al., 2015). A more recent re-analysis of the meta-analytic data, only including healthy adult samples (N = 1758), found a correlation of r = 0.31 (Gignac & Bates, 2017). Furthermore, the correlation increased as a function of intelligence measurement quality: studies with better-quality intelligence tests—for instance, those including multiple measures and a longer testing time—tended to produce even higher correlations with brain volume (up to 0.39). […] Here, we report an analysis of data from a large, single sample with high-quality MRI measurements and four diverse cognitive tests. […] We judge that the large N, study homogeneity, and diversity of cognitive tests relative to previous large scale analyses provides important new evidence on the size of the brain structure-intelligence correlation. By investigating the relations between general intelligence and characteristics of many specific regions and subregions of the brain in this large single sample, we substantially exceed the scope of previous meta-analytic work in this area. […]

“We used a large sample from UK Biobank (N = 29,004, age range = 44–81 years). […] This preregistered study provides a large single sample analysis of the global and regional brain correlates of a latent factor of general intelligence. Our study design avoids issues of publication bias and inconsistent cognitive measurement to which meta-analyses are susceptible, and also provides a latent measure of intelligence which compares favourably with previous single-indicator studies of this type. We estimate the correlation between total brain volume and intelligence to be r = 0.276, which applies to both males and females. Multiple global tissue measures account for around double the variance in g in older participants, relative to those in middle age. Finally, we find that associations with intelligence were strongest in frontal, insula, anterior and medial temporal, lateral occipital and paracingulate cortices, alongside subcortical volumes (especially the thalamus) and the microstructure of the thalamic radiations, association pathways and forceps minor.”

…

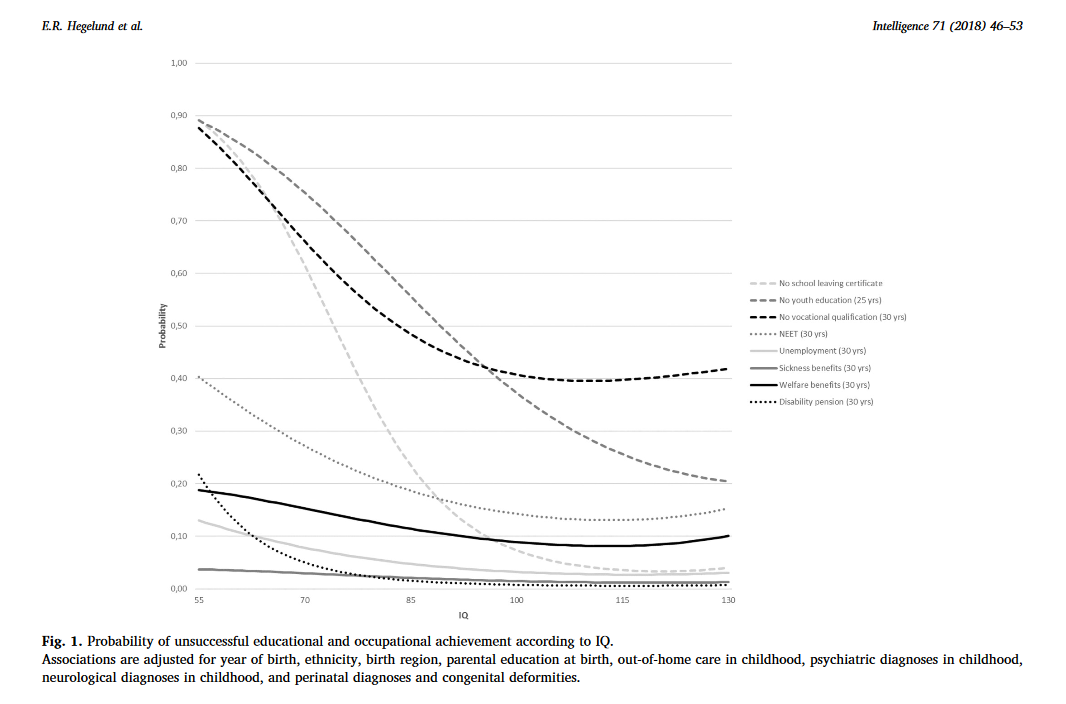

vii. Another IQ study: Low IQ as a predictor of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement: A register-based study of 1,098,742 men in Denmark 1968–2016.

“Intelligence test score is a well-established predictor of educational and occupational achievement worldwide […]. Longitudinal studies typically report cor-relation coefficients of 0.5–0.6 between intelligence and educational achievement as assessed by educational level or school grades […], correlation coefficients of 0.4–0.5 between intelligence and occupational level […] and cor-relation coefficients of 0.2–0.4 between intelligence and income […]. Although the above-mentioned associations are well-established, low intelligence still seems to be an overlooked problem among young people struggling to complete an education or gain a foothold in the labour market […] Due to contextual differences with regard to educational system and flexibility and security on the labour market as well as educational and labour market policies, the role of intelligence in predicting unsuccessful educational and occupational courses may vary among countries. As Denmark has free admittance to education at all levels, state financed student grants for all students, and a relatively high support of students with special educational needs, intelligence might be expected to play a larger role – as socioeconomic factors might be of less importance – with regard to educational and occupational achievement compared with countries outside Scandinavia. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the role of IQ in predicting a wide range of indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement among young people born across five decades in Denmark.”

“Individuals who differed in IQ score were found to differ with regard to all indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement such that low IQ was associated with a higher proportion of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement. For example, among the 12.1% of our study population who left lower secondary school without receiving a certificate, 39.7% had an IQ < 80 and 23.1% had an IQ of 80–89, although these individuals only accounted for 7.8% and 13.1% of the total study population. The main analyses showed that IQ was inversely associated with all indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement in young adulthood after adjustment for covariates […] With regard to unsuccessful educational achievement, […] the probabilities of no school leaving certificate, no youth education at age 25, and no vocational qualification at age 30 decreased with increasing IQ in a cubic relation, suggesting essentially no or only weak associations at superior IQ levels. IQ had the strongest influence on the probability of no school leaving certificate. Although the probabilities of the three outcome indicators were almost the same among individuals with extremely low IQ, the probability of no school leaving certificate approached zero among individuals with an IQ of 100 or above whereas the probabilities of no youth education at age 25 and no vocational qualification at age 30 remained notably higher. […] individuals with an IQ of 70 had a median gross income of 301,347 DKK, individuals with an IQ of 100 had a median gross income of 331,854, and individuals with an IQ of 130 had a median gross income of 363,089 DKK – in the beginning of June 2018 corresponding to about 47,856 USD, 52,701 USD, and 57,662 USD, respectively. […] The results showed that among individuals undergoing education, low IQ was associated with a higher hazard rate of passing to employment, unemployment, sickness benefits receipt and welfare benefits receipt […]. This indicates that individuals with low IQ tend to leave the educational system to find employment at a younger age than individuals with high IQ, but that this early leave from the educational system often is associated with a transition into unemployment, sickness benefits receipt and welfare benefits receipt.”

“Conclusions

This study of 1,098,742 Danish men followed in national registers from 1968 to 2016 found that low IQ was a strong and consistent predictor of 10 indicators of unsuccessful educational and occupational achievement in young adulthood. Overall, it seemed that IQ had the strongest influence on the risk of unsuccessful educational achievement and on the risk of disability pension, and that the influence of IQ on educational achievement was strongest in the early educational career and decreased over time. At the community level our findings suggest that intelligence should be considered when planning interventions to reduce the rates of early school leaving and the unemployment rates and at the individual level our findings suggest that assessment of intelligence may provide crucial information for the counselling of poor-functioning schoolchildren and adolescents with regard to both the immediate educational goals and the more distant work-related future.”

Dyslexia (I)

A few years back I started out on another publication edited by the same author, the Wiley-Blackwell publication The Science of Reading: A Handbook. That book is dense and in the end I decided it wasn’t worth it to finish it – but I also learned from reading it that Snowling, the author of this book, probably knows her stuff. This book only covers a limited range of the literature on reading, but an interesting one.

I have added some quotes and links from the first chapters of the book below.

…

“Literacy difficulties, when they are not caused by lack of education, are known as dyslexia. Dyslexia can be defined as a problem with learning which primarily affects the development of reading accuracy and fluency and spelling skills. Dyslexia frequently occurs together with other difficulties, such as problems in attention, organization, and motor skills (movement) but these are not in and of themselves indicators of dyslexia. […] at the core of the problem is a difficulty in decoding words for reading and encoding them for spelling. Fluency in these processes is never achieved. […] children with specific reading difficulties show a poor response to reading instruction […] ‘response to intervention’ has been proposed as a better way of identifying likely dyslexic difficulties than measured reading skills. […] To this day, there is tension between the medical model of ‘dyslexia’ and the understanding of ‘specific learning difficulties’ in educational circles. The nub of the problem for the concept of dyslexia is that, unlike measles or chicken pox, it is not a disorder with a clear diagnostic profile. Rather, reading skills are distributed normally in the population […] dyslexia is like high blood pressure, there is no precise cut-off between high blood pressure and ‘normal’ blood pressure, but if high blood pressure remains untreated, the risk of complications is high. Hence, a diagnosis of ‘hypertension’ is warranted […] this book will show that there is remarkable agreement among researchers regarding the risk factors for poor reading and a growing number of evidence-based interventions: dyslexia definitely exists and we can do a great deal to ameliorate its effects”.

“An obvious though not often acknowledged fact is that literacy builds on a foundation of spoken language—indeed, an assumption of all education systems is that, when a child starts school, their spoken language is sufficient to support reading development. […] many children start school with considerable knowledge about books: they know that print runs from left to right (at least if you are reading English) and that you read from the front to the back of the book; and they are familiar with at least some letter names or sounds. At a basic level, reading involves translating printed symbols into pronunciations—a task referred to as decoding, which requires mapping across modalities from vision (written forms) to audition (spoken sounds). Beyond knowing letters, the beginning reader has to discover how printed words relate to spoken words and a major aim of reading instruction is to help the learner to ‘crack’ this code. To decode in English (and other alphabetic languages) requires learning about ‘grapheme–phoneme’ correspondences—literally the way in which letters or letter combinations relate to the speech sounds of spoken words: this is not a trivial task. When children use language naturally, they have only implicit knowledge of the words they use and they do not pay attention to their sounds; but this is precisely what they need to do in order to learn to decode. Indeed, they have to become ‘aware’ that words can be broken down into constituent parts like the syllable […] and that, in turn, syllables can be segmented into phonemes […]. Phonemes are the smallest sounds which differentiate words; for example, ‘pit’ and ‘bit’ differ by a single phoneme [b]-[p] (in fact, both are referred to as ‘stop consonants’ and they differ only by a single phonemic feature, namely the timing of the voicing onset of the consonant). In the English writing system, phonemes are the units which are coded in the grapheme-correspondences that make up the orthographic code.”

“The term ‘phoneme awareness‘ refers to the ability to reflect on and manipulate the speech sounds in words. It is a metalinguistic skill (a skill requiring conscious control of language) which develops after the ability to segment words into syllables and into rhyming parts […]. There has been controversy over whether phoneme awareness is a cause or a consequence of learning to read. […] In general, letters are easier to learn (being concrete) than phoneme awareness is to acquire (being an abstract skill). […] The acquisition of ‘phoneme awareness’ is a critical step in the development of decoding skills. A typical reader who possesses both letter knowledge and phoneme awareness can readily ‘sound out’ letters and blend the sounds together to read words or even meaningless but pronounceable letter strings (nonwords); conversely, they can split up words (segment them) into sounds for spelling. When these building blocks are in place, a child has developed ‘alphabetic competence’ and the task of becoming a reader can begin properly. […[ Another factor which is important in promoting reading fluency is the size of a child’s vocabulary. […] children with poor oral language skills, specifically limited semantic knowledge of words, [have e.g. been shown to have] particular difficulty in reading irregular words. […] Essentially, reading is a ‘big data’ problem—the task of learning involves extracting the statistical relationships between spelling (orthography) and sound (phonology) and using these to develop an algorithm for reading which is continually refined as further words are encountered.”

“It is commonly believed that spelling is simply the reverse of reading. It is not. As a consequence, learning to read does not always bring with it spelling proficiency. One reason is that the correspondences between letters and sounds used for reading (grapheme–phoneme correspondences) are not just the same as the sound-to-letter rules used for writing (phoneme–grapheme correspondences). Indeed, in English, the correspondences used in reading are generally more consistent than those used in spelling […] many of the early spelling errors children make replicate errors observed in speech development […] Children with dyslexia often struggle to spell words phonetically […] The relationship between phoneme awareness and letter knowledge at age 4 and phonological accuracy of spelling attempts at age 5 has been studied longitudinally with the aim of understanding individual differences in children’s spelling skills. As expected, these two components of alphabetic knowledge predicted the phonological accuracy of children’s early spelling. In turn, children’s phonological spelling accuracy along with their reading skill at this early stage predicted their spelling proficiency after three years in school. The findings suggest that the ability to transcode phonologically provides a foundation for the development of orthographic representations for spelling but this alone is not enough—information acquired from reading experience is required to ensure spellings are conventionally correct. […] for spelling as for reading, practice is important.”

“Irrespective of the language, reading involves mapping between the visual symbols of words and their phonological forms. What differs between languages is the nature of the symbols and the phonological units. Indeed, the mappings which need to be created are at different levels of ‘grain size’ in different languages (fine-grained in alphabets which connect letters and sounds like German or Italian, and more coarse-grained in logographic systems like Chinese that map between characters and syllabic units). Languages also differ in the complexity of their morphology and how this maps to the orthography. Among the alphabetic languages, English is the least regular, particularly for spelling; the most regular is Finnish with a completely transparent system of mappings between letters and phonemes […]. The term ‘orthographic depth’ is used to describe the level of regularity which is observed between languages — English is opaque (or deep), followed by Danish and French which also contain many irregularities, while Spanish and Italian rank among the more regular, transparent (or shallow) orthographies. Over the years, there has been much discussion as to whether children learning to read English have a particularly tough task and there is frequent speculation that dyslexia is more prevalent in English than in other languages. There is no evidence that this is the case. But what is clear is that it takes longer to become a fluent reader of English than of a more transparent language […] There are reasons other than orthographic consistency which make languages easier or harder to learn. One of these is the number of symbols in the writing system: the European languages have fewer than 35 while others have as many as 2,500. For readers of languages with extensive symbolic systems like Chinese, which has more than 2,000 characters, learning can be expected to continue through the middle and high school years. The visual-spatial complexity of the symbols may add further to the burden of learning. […] when there are more symbols in a writing system, the learning demands increase. […] Languages also differ importantly in the ways they represent phonology and meaning.”

“Given the many differences between languages and writing systems, there is remarkable similarity between the predictors of individual differences in reading across languages. The ELDEL study showed that for children reading alphabetic languages there are three significant predictors of growth in reading in the early years of schooling. These are letter knowledge, phoneme awareness, and rapid naming (a test in which the names of colours or objects have to be produced as quickly as possible in response to a random array of such items). Researchers have shown that a similar set of skills predict reading in Chinese […] However, there are also additional predictors that are language-specific. […] visual memory and visuo-spatial skills are stronger predictors of learning to read in a visually complex writing system, such as Chinese or Kannada, than they are for English. Moreover, there is emerging evidence of reciprocal relations – that learning to read in a complex orthography hones visuo-spatial abilities just as phoneme awareness improves as English children learn to read.”

“Children differ in the rate at which they learn to read and spell and children with dyslexia are typically the slowest to do so, assuming standard instruction for all. Indeed, it is clear from the outset that they have more difficulty in learning letters (by name or by sound) than their peers. As we have seen, letter knowledge is a crucial component of alphabetic competence and also offers a way into spelling. So for the dyslexic child with poor letter knowledge, learning to read and spell is compromised from the outset. In addition, there is a great deal of evidence that children with dyslexia have problems with phonological aspects of language from an early age and specifically, acquiring phonological awareness. […] The result is usually a significant problem in decoding—in fact, poor decoding is the hallmark of dyslexia, the signature of which is a nonword reading deficit. In the absence of remediation, this decoding difficulty persists and for many reading becomes something to be avoided. […] the most common pattern of reading deficit in dyslexia is an inability to read ‘new’ or unfamiliar words in the face of better developed word-reading skills — sometimes referred to as ‘phonological dyslexia’. […] Spelling poses a significant challenge to children with dyslexia. This seems inevitable, given their problems with phoneme awareness and decoding. The early spelling attempts of children with dyslexia are typically not phonetic in the way that their peers’ attempts are; rather, they are often difficult to decipher and best described as bizarre. […] errors continue to reflect profound difficulties in representing the sounds of words […] most people with dyslexia continue to show poor spelling through development and there is a very high correlation between (poor) spelling in the teenage years and (poor) spelling in middle age. […] While poor decoding can be a barrier to reading comprehension, many children and adults with dyslexia can read with adequate understanding when this is required but it takes them considerable time to do so, and they tend to avoid writing when it is possible to do so.”

…

Links:

Phonics.

History of dyslexia research. Samuel Orton. Rudolf Berlin. Anna Gillingham. Orton-Gillingham(-Stillman) approach. Thomas Richard Miles.

Seidenberg & McClelland’s triangle model.

“The Simple View of Reading”.

The lexical quality hypothesis (Perfetti & Hart). Matthew effect.

ELDEL project.

Diacritical mark.

Hiragana.

Phonetic radicals.

Morphogram.